"Enjoy failure and learn from it. You never learn from success."

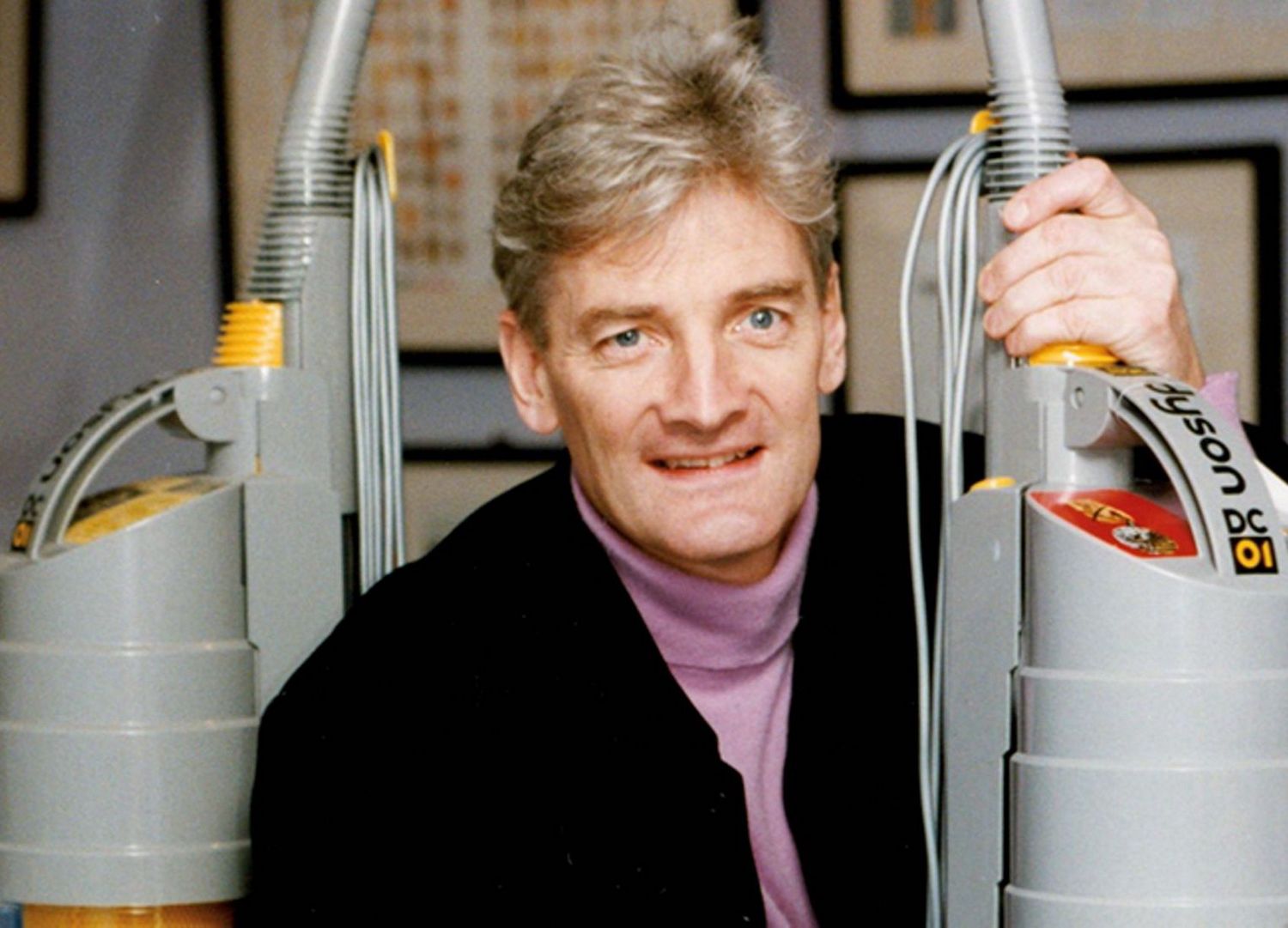

Sir James Dyson

Sir James Dyson biography

Sir James Dyson is an inventor, entrepreneur and philanthropist who has devoted his life to solving problems and developing products through the application of new technologies.

He is Founder and Chairman of Dyson, a problem solving, technology-led, company which is present in 84 markets around the world. Around half of the global Dyson team are engineers and scientists, and its research interests span robotics, AI, machine learning, solid state battery development, material science and high-speed electric motors.

James Dyson established Dyson Farming in 2013, as a commercial farming business driving efficiency and sustainability in UK agriculture. The business is focused on creating tasty, high quality food with a low environmental impact, as well being good custodians of the land over the long term – encouraging biodiversity and innovation in farming.

He established the James Dyson Foundation in 2002, to challenge misconceptions about engineering and inspire more young people to pursue careers in engineering and science, it runs the annual global James Dyson Award to celebrate and support young problem-solving inventors in sustainability

and medical fields.

In 2017, Dyson founded the Dyson Institute of Engineering and Technology, based on the Dyson Campus in Malmesbury. It is a new form of degree, in which school leavers study while undertaking a full-time salaried role in Dyson’s engineering team. The first cohort graduated in 2021 and all elected to remain at Dyson.

James was awarded a CBE in 1996 and a Knight Bachelor in 2007. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 2015, and in the 2016 New Year Honours was appointed to the Order of Merit – the highest honour and the only one within the Queen’s personal gift.

James and his wife Deirdre have three children - Emily, Jake and Sam - and six grandchildren.

Sir James Dyson has devoted his life to developing products and companies that solve problems.

He grew up exploring the marshes and sand dunes of the rural North Norfolk coastline. It was here that he discovered his passion for competitive long-distance running – a discipline that taught him about determination.

“The time to push hard is when you’re hurting like crazy and you want to give up, because success is often just around the corner.”

James attended Gresham’s school where his father, Alec, taught classics. After losing his father to cancer at the age of nine, Gresham’s provided a bursary for James to stay at the school – generosity that he later recognised through a £18.75m donation to enable the construction of the Dyson STEAM building at the school, which was conceived by the late architect and friend, Chris Wilkinson.

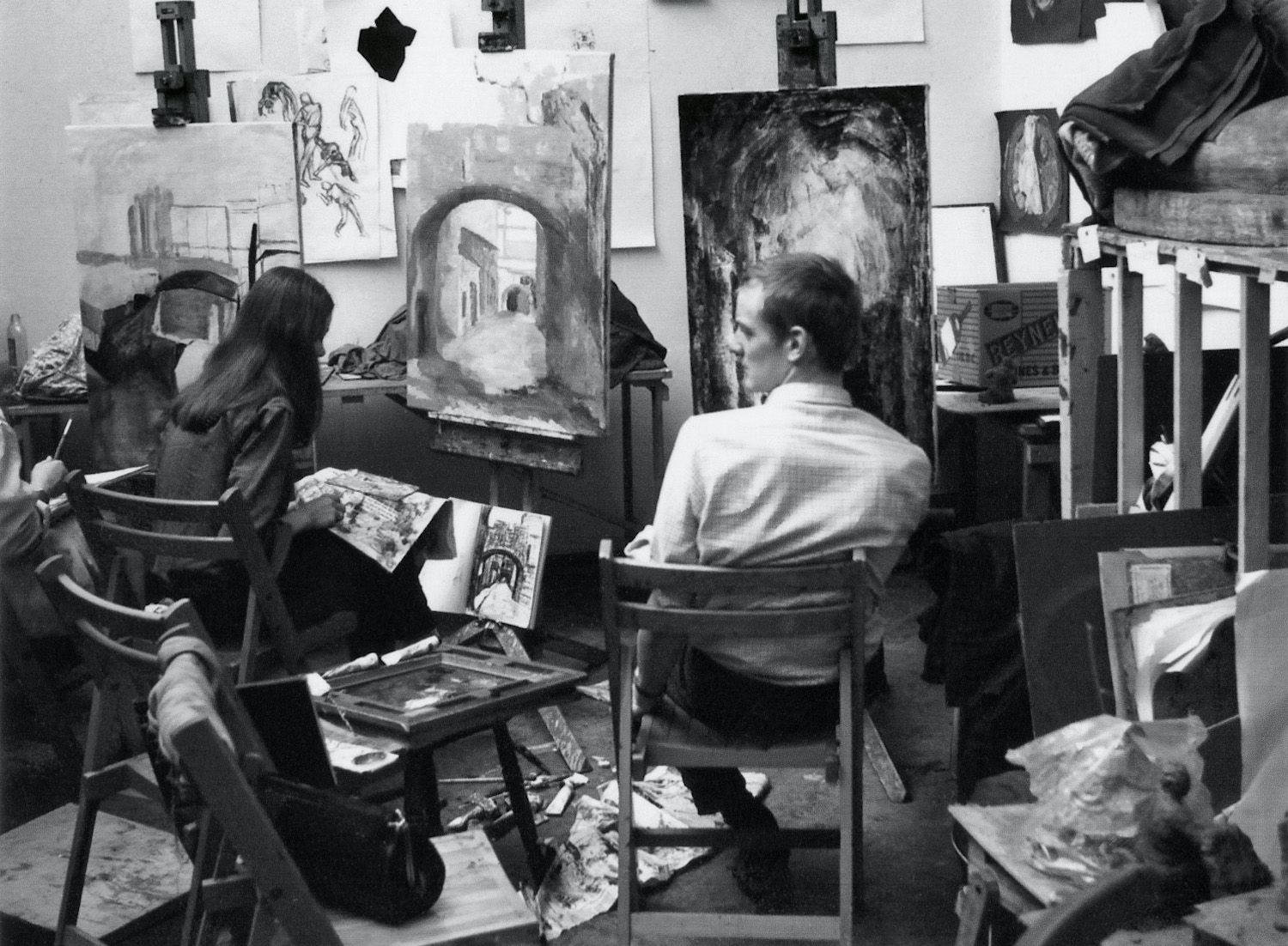

After Gresham’s, James earned a place to study at the Byam Shaw School of Art (1965–66) before studying architectural design at the Royal College of Art (1966–70). It was during this time that a life-long obsession with functional design and engineering developed but also where he met his future wife and greatest supporter, Deirdre.

At the Royal College of Art, James developed a unique design for a mushroom shaped theatre building for Joan Littlewood; he approached British inventor and engineer, Jeremy Fry, for funding for the project. Fry turned down the theatre and instead asked James to design a versatile high-speed landing craft, which would become known as the Sea Truck.

Fry became a mentor to James and on leaving the Royal College of Art, with no relevant experience, he asked James to head-up the new Marine Division of his company, Rotork. The challenge of designing, manufacturing and selling the Sea Truck around the world equipped James with the resilience and determination he’d later rely on when starting his own venture.

His idea for an unconventional plastic barrow – with a ball rather than a wheel – ultimately drew James away from the safety and comfort of a salary. He went it alone in 1974. The Ballbarrow went against the grain and overcame many of the problems with traditional wheelbarrows. It featured the world’s first load-spreading, pneumatic ball instead of a narrow wheel which, together with wide legs, prevented it from sinking into soft ground.

At the same time, James and Deirdre were busy raising a family after the birth of their daughter Emily and their sons Jake and Sam. Despite the added pressure of family life, James continued to invent alone, creating a range of new machines such as the Wheelboat, which James was prevented from commercialising as the project was deemed to be of military significance.

It was in 1978 when one of the most important moments of his life as an inventor came about. While spraying the Ballbarrow’s metal frames with powdered paint, he became frustrated by the way excess powder would miss the frames and get caught in the calico cloth behind and become clogged. It was wasteful, so James investigated a better way.

Inspired by an expensive industrial cyclone he’d seen at a local timber mill, he decided to make a version himself, building a 25ft cyclone to suck the waste powder away. This was, as he would later describe, “a form of filter that never clogged.”

‘The filter that never cloggs’ on the roof of Hill Leigh Ltd. sawmill

At the same time, a similar problem presented itself in the Dyson household. After purchasing a top-of-the-range Hoover vacuum cleaner, James was frustrated to discover that the non-reusable bag frequently clogged with dust and dirt. Keen to understand if the same technology he had installed in the Ballbarrow factory could be applied to vacuum cleaners, James constructed a rudimentary cyclone made from cardboard and strapped it to his upright vacuum cleaner in place of the bag. It proved a seminal moment and four years and 5,127 prototypes later, the first cyclonic vacuum cleaner was ready for production – but would any manufacturer take a risk on it?

The vacuum cleaner bag market was worth over $500m in Europe alone at the time and James’ designs for a cyclonic vacuum were rejected by all major vacuum manufacturers. Undeterred, James persevered amidst the rejection – once again, he would have to go it alone. In 1993, his first mass-produced vacuum cleaner – DC01 - was launched, and Dyson was in business.

Since then, James has spent his time with growing teams of engineers and scientists, inventing products that harness radical, new technologies to solve problems. The team has pioneered new approaches to traditional products, including low-energy cordless vacuums, bladeless fans, air purifiers, heaters, and, most recently, lighting, high efficiency hair dryers, stylers and straighteners.

Scientific research by Dyson’s growing team of engineers and scientists has led to breakthroughs in the fields of digital motors, solid state batteries, material science and purification. Now present in 84 markets, Dyson has grown into a global technology company, headquartered in Singapore, but with a significant footprint also in the UK, Philippines, and Malaysia.

In keeping with the strong design philosophy that underlines Dyson as a company, James developed a close partnership with the late architect Chris Wilkinson, who helped bring James’ vision and values to life in the company’s many buildings around the world. Standing by James’ side at every point in Dyson’s expansion, Wilkinson helped to create Dyson’s UK campus in Malmesbury – with its wavy roofed main building and pioneering clean air system; the daring, structural glass D9 building; the Undergraduate Village of cross-laminated factory-built pods; the Roundhouse clubhouse, and the faithful restoration of the vast hangars at Hullavington Airfield. While hugely varied, each project reflected Wilkinson’s belief that buildings should be a marriage of architecture, art, design and technology and James’ belief that engineers and scientists should work side-by-side in inspiring surroundings.

St.James Power Station, Singapore; The Wilkinson Building, Malmesbury, UK; Dyson's Malmesbury campus, Malmesbury, UK; Dyson student accommodation, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, UK; STEAM Building, Gresham School, Holt, Norfolk.

“Success tells you nothing. Failure is interesting – it’s part of making progress. You never learn from success, but you do learn from failure.”

Despite the growth of Dyson and James’ accomplishments over the years, his path to success has not been without failure.

Alongside the 5,126 failed vacuum prototypes that paved the way to his most notable success story, James’ has continued to learn from failure. Inventing the Contrarotator washing machine in 2000, the revolutionary machine featured two large counter-rotating drums that could clean bigger loads better and faster than any of its competitor at the time. Although it was pioneering in terms of its technology, it was not a commercial success and high manufacturing costs meant that production finally ceased.

More recently, in 2014, James developed plans for a radical new battery-electric vehicle. Investing over £500m in the project in less than five years, the car was developed to a pre-production level and measured five metres in length with generous ground clearance and room for seven adults inside. With a 150kWh battery, the car would travel over 600 miles on a single charge and would have been developed at Dyson’s newly acquired and faithfully restored Hullavington airfield, close to its Malmesbury campus in Wiltshire. Like many of his inventions before it, the pioneering technology behind the car and the lessons learnt from its creation were invaluable and would live on, but ultimately the Dyson car was not commercially viable and the project was halted in 2019.

-

2000: Dyson Contrarotator washing machine

-

2020: The Dyson Battery Electric Vehcile

These lessons, learnt on his journey as an inventor over the years, occupy the pages of books James has written. His first, Doing a Dyson, was written by James and also Tony Muranka in 1996, and was promptly followed by his first autobiography, Against the Odds, in 1997. In 2001, James wrote and published A History of Great Inventions and in 2010, he co-presented the Channel Four TV series, Genius of Britain. In 2021, a second autobiography, Invention: A Life, was published and quickly entered The Sunday Times bestseller list.

James has long been a keen advocate of the importance of engineering education, and established the James Dyson Foundation in 2002, to inspire more young people to pursue careers in engineering and science. The James Dyson Foundation inspires the next generation of engineers through its work in schools and universities. Its scholarships, engineering workshops, university partnerships and the annual James Dyson Award – an international student engineering problem solving competition – aim to inspire, encourage and aid future engineering talent all around the world.

James has supported higher education institutions by providing funds for new activities and facilities including The Dyson Building at the Royal College of Art (2013), The Dyson School of Design Engineering at Imperial College London (2015) and The Dyson Centre for Engineering Design at Cambridge University in (2016). Since its creation, the Royal College of Art’s incubator housed in the Dyson Building has the largest number of active spinouts of any of the UK university incubators and is third in terms of the number of deals secured by its spinouts. In 2014, James provided the funding for a new professorship – the Dyson Chair of Design Engineering – at the University of Bath.

Outside of education, James’ long-term support and investment into healthcare has led to pioneering new medical research and facilities. Significant amongst them were the development of the Dyson Cancer Centre and the Dyson Centre for Neonatal Care at the Royal United Hospitals Bath (RUH). More recently, his support of his friend and ex-Formula One driver Jackie Stewart’s charity Race Against Dementia created a research Fellowship, which saw Dyson fund and support a research programme with Dr Claire Durrant. By combining biological research with an engineer’s mindset, the partnership is pioneering new research approaches – including a novel approach to human brain slicing – to establish new models of Alzheimer’s disease and speed up the delivery of pioneering research in the field.

The Dyson Institute of Engineering and Technology – based on the Dyson campus in Wiltshire, UK – is perhaps the most significant manifestation of James’ commitment to education. It is a new approach to education, born out of a conversation between James Dyson and Jo Johnson, the then UK Universities Minister after James bemoaned the shortage of engineers in the UK. Jo suggested James start his own university, using new legislation passing through the Houses of Parliament. The Dyson Institute of Engineering and Technology launched in 2017 and was the first institution of its kind anywhere in the world.

The first Dyson Institute of Engineering and Technology cohort graduate

Dyson’s undergraduate engineers pay zero tuition fees and earn a full salary. As well as their degree studies, they work on real-life projects alongside world-experts in Dyson’s global engineering, research and technology teams. From day one they contribute to new technologies to improve lives around the world. It is more than a job, and more than a degree, and although the aspiration is that they remain long after graduation, they are not tied to Dyson.

James has also applied his engineering mindset to other fields and industries, such as farming and food production. Realising the vital role that sustainable farming, food security and the environment play in the nation’s health and the economy, he sees Dyson Farming as an opportunity for technology to drive a revolution in agriculture and vice versa.

Through the application of technology, Dyson farming has developed a highly efficient, carbon neutral circular farming system. The latest evolution is a 15-acre glasshouse that produces 750 tonnes of British strawberries outside the usual growing season, using renewable electricity and surplus heat from an anaerobic digestor. The farm produces flavoursome strawberries without the unnecessary air miles associated with imported fruit. The farms also produce maize, wheat, sugar beet, peas, cabbages and potatoes alongside other crops, cattle and sheep while the anaerobic digestors produce approximately 41,610 MWh per year of sustainable electricity, which is enough to power 10k homes.

James Dyson beside the Anerobic Digester at the Dyson farm in Carrington

In acknowledgement of his services and life’s work, James was awarded a CBE in 1996 and a Knight Bachelor in 2007. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 2015, and in the 2016 New Year Honours was appointed to the Order of Merit - the highest honour and the only one within the Queen’s personal gift. Alongside his national accolades, James was unanimously voted in as Chair of the Design Museum, a position that he occupied from 1999 to 2004. He was appointed Provost of his former alma mater the Royal College of Art in 2010.

James continues to spend his time developing technologies alongside the growing teams of engineers and scientists around the world. Marking the beginning of a new chapter for Dyson, James, Jake and the many Dyson employees based in Singapore move into the historic St James Power Station in 2022. The faithfully restored building is Dyson’s global headquarters, complimenting its significant spaces in the UK, Malaysia, the Philippines and many other countries around the world.

As Dyson continues to grow and expand, it is James’ firmly-held belief in the ability of engineers and scientists to improve the world that continues to drive him forward. Through the work of the Dyson Institute, the James Dyson Foundation, and the James Dyson Award, he hopes to inspire and encourage the next generation to take action and solve the problems they are so passionate about.

For permission to reproduce any content on these pages, please contact the Dyson Press Office.

.jpg)